A long apprenticeship is the most logical way to success. The only alternative is overnight stardom, but I can’t give you a formula for that.

A long apprenticeship is the most logical way to success. The only alternative is overnight stardom, but I can’t give you a formula for that.

Chet Atkins

Once upon a time … learning a skill, including in the healing arts, was a task that was taught by a master to his / her apprentices. Apprenticeships were a mix of learning theoretical knowledge (what tools were best for which purpose and why, what ingredients could be found were, in what ratio would things have to be mixed to be effective) and practical experience (how do you apply this material, how do you handle the tool to the best effect, how do you create the best product with the least effort).

In those days only few people had an opportunity to learn something beyond their familiar skills and it was relatively easy for a master to find apprentices and to create a program of learning that was tailor-made for those apprentices.

When more people wanted to learn and more masters had to be found to teach them, schools offered a good alternative. The theoretical things could be taught to many — in academies, monasteries, and other places of higher learning. Practical skills then often were acquired in subsequent years of supervised practice or apprenticeship with a master. Modern medicine and law still follow that principle with residency and articling times after graduation from university.

The basic idea of this form of training was and is that certain skills simply cannot be taught in theory. As Bruce Lee put it:

Knowing is not enough; we must apply. Willing is not enough; we must do.

I still remember seeing my first client “flying solo” after graduation from my psychotherapy training program. Back in 2000 there were no rules about supervision in the field of psychotherapy in Ontario and so, upon graduation I had ceased to be supervised. I was working in a setting with many colleagues around me and I knew that I could talk to them about any issues I had in my sessions — but that wasn’t quite the same as having the support of a supervisor who knew my clients and my own style and story and could help me see how things were progressing in my work.

So, there I was, my first own, unsupervised client walking through the door and inside of me there was that battle of pride and fear — “I made it, I am a graduated, independent therapist, I can do this” vs. “what the @#*? am I thinking, will I be able to help this person, will I even be able to figure out what he wants help with?” I managed to get through that session and through many sessions after. I learned and I grew. I made mistakes and had successes. I consulted with colleagues on occasion and I read a lot. But often, very often, I wished I had that one person I could turn to, who knew my background, my theoretical orientation, my struggles, my insights, my clients. That person who could help me better understand my clients, my work, myself as a therapist.

Five years later I became a supervisor for therapists in training and I tried to give them what I had been looking for over those past five years. I probably didn’t succeed all the time but working with these therapists-to-be renewed my belief that some of the things we need to master in order to become good therapists can’t be learned in theory; it needs to be learned in practice.

Now, as a supervisor working with psychotherapists who are in the processes of qualifying for membership in the CRPO1 or with counsellors who are looking to becoming members of a counsellors’ association such as the CPCA, I still see my main task as offering a platform for an apprenticeship of sorts.

Therapy and supervision aren’t that different in their essence: both require the client to open up and share of themselves and their inner processes; both require the practitioner (the therapist or supervisor) to listen carefully, listen behind the verbally and consciously expressed, to see the whole picture. However, the supervisor has to do this twice, so to speak: listen to and see the whole picture of the therapist in front of him / her and that therapist’s work and practice; and listen to and see the bigger picture of that therapist’s clients and their lives and issues.

This second step is important because the supervisor is also responsible to a degree for the supervisee’s clients’ well-being. That responsibility sometimes creates worries and fear in the supervisor and so it can get in the way of doing effective supervision. If I am more afraid of the responsibility I have toward a person I have never met (the therapist’s client), if all my energy goes into trying to figure out what to do with that client, I can easily overlook the important part of supervision: offering the therapist in front of me a chance to learn how to work with this client out of his / her own set of capabilities, skills, and observations.

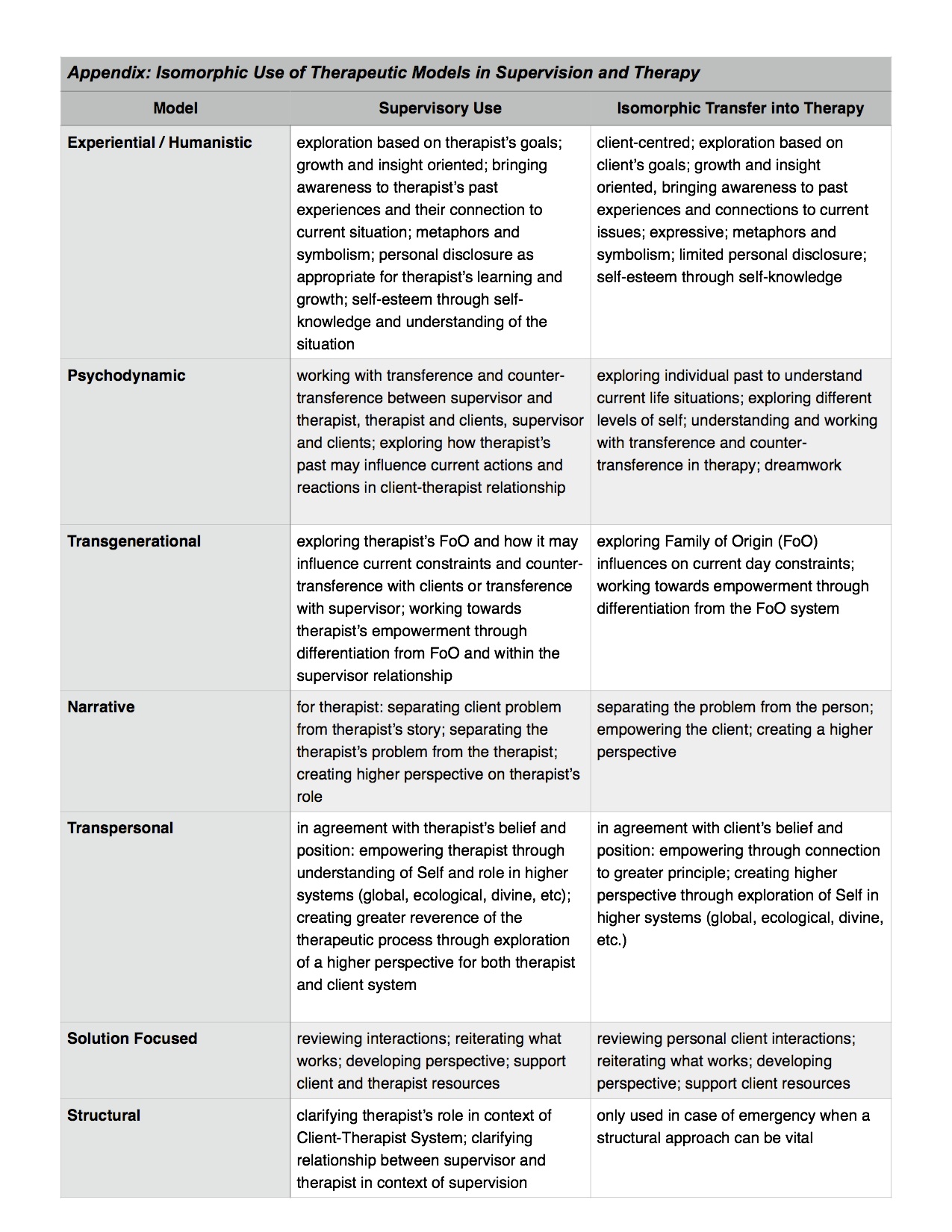

Every supervisory relationship is different and unique, just like every client relationship is different and unique. In working with therapists in supervision there are clear parallels between client work and supervisory work. The table below is an excerpt from a paper I wrote as part of my supervisor training outlining the parallels in my own work with clients and with supervisees.

Not every one of those tools will be used in every supervisory relationship. But the importance to me isn’t in the tools anyway. It is in the energy of it: all the descriptions of supervision are active. The supervisory process, in my understanding, is one of active learning, of exploring, of growing, even of making mistakes. Like in the practice of doing therapy with clients, supervision can not be divorced from the therapist’s own inner work. Learning how to bring our own experiences and questions into our work and how to keep our own challenges and projections out of it, that is only possible when we reflect on that work. Reflecting on our work is most helpful when it is done with a witness — and supervision is the perfect place to do this witnessed reflection in the safety of a trusting relationship. How that relationship is build does not depend on the tools used as much as it depends on the active participation of both parties in the relationship.

That last statement begs the question: How do you find the right supervisor for yourself?

Again, the answer is actually quite similar to the parallel one in therapy: How do you find the right therapist for yourself? These are some of the points I believe to be important:

- Look for someone whose philosophy of therapy and of life is similar to yours. This is important because you want to be understood in the way that you approach your work. E.g., if you are practicing based on a strictly secular and science based background, having a supervisor who is faith-based and works with spiritual tools will necessitate a lot of additional explanations, discussions and finding common ground.

- Look for a supervisor whose supervision requirements align with your possibilities. E.g., if your supervisor expects you to video record your sessions but you don’t have the technological tools to do so or you work with a client base that is very suspicious of such technology, you will create a lot of unnecessary tension right from the start.

- Look for a supervisor who has the level of experience you want and expect. The CRPO and most associations have requirements for supervisors that include “extensive practice”, usually five years or more. But make sure that this practice is in the area of work you are looking for. E.g., wanting to start a practice in family therapy? Make sure the supervisor you choose is a family therapist. Want to work with clientele from a specific cultural background? Does your chosen supervisor understand that culture, does she / he have experience working with that clientele?

- Look for supervision you can afford. Depending on your reasons for supervision, the supervisory relationship is usually long-term and frequent2. Contracts are often signed for a one-year period to keep therapists from “jumping around” and avoiding in-depth supervision of their work. So it becomes important to ensure that you can afford your supervision in the long term. There are different choices: individual one-on-one sessions are usually more effective but also are more expensive; group supervision usually is the most affordable but it may require some additional one-on-one work in order to provide the depth of supervision you need or desire.

- Finally, look for a supervisor with whom you “click”. The supervisory relationship is one of the most important relationships on your path towards becoming a master in psychotherapy yourself. You have to be able to challenge your supervisor and you have to be willing to be challenged by him / her. You have to trust that he / she will be truthful and honest without being harsh or hurtful. You have to be able to relate to her / him without projecting too much of your own issues on her / him (e.g. any fear of authorities, mom or dad issues, etc.). Your supervisor should be a colleague for you first; a colleague with more experience, a colleague with your best interest at heart.

The more you trust your supervisor and connect with her / him, the better your chances that you’ll grow and thrive in the supervisory relationship. The more you put into your apprenticeship during supervision, the better and faster you will hone your skills as a psychotherapist.

Somewhere along the line you’ve got to do your apprenticeship. But I’d want half a chance of being successful at it.

Alan Shearer

1Clinical Supervisor Competency Requirements

On April 1, 2018, CRPO will phase in new requirements for qualifying as a clinical supervisor. Specifically, clinical supervisors will need to demonstrate competence in providing clinical supervision.

CRPO’s Registration Committee has approved the following criteria for demonstrating competence in providing clinical supervision:

1. The supervisor must be a Member in good standing of a regulatory college whose members may practise psychotherapy.*

2. The supervisor must have five years’ extensive clinical experience.

3. The supervisor must meet CRPO’s “independent practice” requirement (completion of 1000 direct client contact hours and 150 hours of clinical supervision).

4. The supervisor must have completed 30 hours of directed learning in providing clinical supervision. Directed learning can include course work, supervised practice as a clinical supervisor, individual/peer/group learning, and independent study that includes structured readings.

5. The supervisor must provide a signed declaration that they understand CRPO’s definitions of clinical supervision, clinical supervisor, and the scope of practice of psychotherapy.

CRPO staff may request evidence of 30 hours of directed learning in providing clinical supervision and may also request a letter of verification and a statement describing the supervisor’s approach to providing supervision.

It is recommended that a clinical supervisor be able to provide their supervisee with a letter attesting to their competency, as set out in 1 through 5 above, that the supervisee would submit as evidence of supervision in the supervisee’s application to CRPO.

*College of Nurses of Ontario; College of Occupational Therapists of Ontario; College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario; College of Psychologists of Ontario; College of Registered Psychotherapists of Ontario; Ontario College of Social Workers and Social Service Workers.

Criteria 3-5 listed above will not take effect until April 1, 2018. Supervision received prior to this date must be provided by a Member in good standing of one of the regulatory colleges whose members may practise psychotherapy, who has extensive clinical experience (generally five years or more) in the practice of psychotherapy and who is competent in providing clinical supervision, in order for those hours to count for registration purposes with CRPO.

(from CRPO’s communique of September 2016)

2Clinical Supervision

Clinical supervision means a contractual relationship in which a clinical supervisor engages with a supervisee to:

- promote the professional growth of the supervisee

- enhance the supervisee’s safe and effective use of self in the therapeutic relationship

- discuss the direction of therapy, or

- safeguard the well-being of the client.

Clinical Supervision can be individual, dyadic or group.

Three years after proclamation, a clinical supervisor must be a regulated practitioner in psychotherapy in good standing with her or his College, who has extensive clinical experience, generally five years or more, in the practice of psychotherapy, and who has demonstrated competence in providing clinical supervision.

(from CRPO’s website: http://www.crpo.ca/home/info-for-applicants/definitions/)